Namespace Logic¶

For a blockchain solution of internet scale to be realizable, it, like the internet, must possess a logic to reason about the “location” of a resource. Specifically, how do we reference a resource? How do we determine which agents can access that resource under what conditions? In contrast to many other blockchains, where addresses are flat public keys (or hashes thereof), RChain’s virtual address space will be partitioned into namespaces. In a very general explanation, a namespace is a set of named channels. Because channels are quite often implemented as data stores, a namespace is equivalently a set of contentious resources.

We have established that two processes must share a named channel to communicate, but what if multiple processes share the same channel? Transactional nondeterminism is introduced under two general conditions which render a resource contentious and susceptible to race conditions:

for(ptrn <- x){P1} | x!(@Q) | for(ptrn <- x){P2}

The first race condition occurs when multiple clients in parallel composition compete to receive a data resource on a named channel. In this case P1 and P2 , are waiting, on the named channel x, for the resource @Q being sent on x by another process. The clients will execute their continuations if and only if the correct value is witnessed at that location. In other cases where many clients are competing, many reductions may be possible, but, in this case, only one of two may result. One where P1 receives @Q first and one where P2 receives @Q first, both of which may return different results when @Q is substituted into their respective protocol bodies.

x!(@Q1) | for(ptrn <- x){P} | x!(@Q2)

The second race condition occurs when two clients compete to send a data resource on a named channel. In this case, two clients are each competing to send a data resource @Q to the client at the named channel x, but only one of two transactions may occur - one where the receiving client receives @Q1 first and one where it receives @Q2 first, both of which may return different results when substituted into the protocol body of P.

For protocols which compete for resources, this level of nondeterminism is unavoidable. Later, in the section on consensus, we will describe how the consensus algorithm maintains replicated state by converging on one of the many possible transaction occurrences in a nondeterministic process. For now, observe how simply redefining a name constrains reduction in the first race condition:

for(ptrn <- x){P1} | x!(@Q) | for(ptrn <- v){P2} → P1{ @Q/ptrn } | for(ptrn <- v){P2}

–and the second race condition:

x!(@Q1) | for(ptrn <- x){P} | u!(@Q2) → P{ @Q1/ptrn } | u!(@Q2)

In both cases, the channel, and the data resource being communicated, is no longer contentious simply because they are now communicating over two distinct, named channels. In other words, they are in separate namespaces. Additionally, names are provably unguessable, so they can only be acquired when a discretionary external process gives them. Because a name is unguessable, a resource is only visible to the processes/contracts that have knowledge of that name [5]. Hence, sets of processes that execute over non-conflicting sets of named channels i.e sets of transactions that execute in separate namespaces, may execute in parallel, as demonstrated below:

for(ptrn1 <- x1){P1} | x1!(@Q1) | ... | for(ptrnn <- xn){Pn} | xn!(@Qn) → P1{ @Q1/ptrn1} | ... | Pn{ @Qn/ptrnn }

| for(ptrn1 <- v1){P1} | v1!(@Q1) | ... | for(ptrnn <- vn){Pn} | vn!(@Q1) → P1{ @Q1/ptrn1} | ... | Pn{ @Qn/ptrnn }

The set of transactions executing in parallel in the namespace x, and the set of transactions executing in the namespace v, are double-blind; they are anonymous to each other unless introduced by an auxillary process. Both sets of transactions are communicating the same resource, @Q, and even requiring that @Q meets the same ptrn, yet no race conditions arise because each output has a single input counter-part, and the transactions occur in separate namespaces. This approach to isolating sets of process/contract interactions essentially partitions RChain’s address space into many independent transactional environments, each of which are internally concurrent and may execute in parallel with one another.

Still, in this representation, the fact remains that resources are visible to processes/contracts which know the name of a channel and satisfy a pattern match. After partitioning the address space into a multiplex of isolated transactional environments, how do we further refine the type of process/contract that can interact with a resource in a similar environment? – under what conditions, and to what extent, may it do so? For that we turn to definitions.

Namespace Definitions¶

A namespace definition is a formulaic description of the minimum conditions required for a process/contract to function in a namespace. In point of fact, the consistency of a namespace is immediately and exclusively dependent on how that space defines a name, which may vary greatly depending on the intended function of the contracts the namespace definition describes.

A name satisfies a definition, or it does not; it functions, or it does not. The following namespace definition is implemented as an ‘if conditional’ in the interaction which depicts a set of processes sending a set of contracts to a set of named addresses that comprise a namespace:

- A set of contracts,

contract1...contractn, are sent to the set of channels (namespace)address1...addressn. - In parallel, a process listens for input on every channel in the

addressnamespace. - When a contract is received on any one of the channels, it is supplied to

if cond., which checks the namespace origin, the address of sender, the behavior of the contract, the structure of the contract, as well as the size of data the contract carries. - If those properties are consistent with those denoted by the

addressnamespace definition, continuationPis executed withcontractas its argument.

A namespace definition effectively bounds the types of interactions that may occur in a namespace - with every contract existing in the space demonstrating a common and predictable behavior. That is, the state alterations invoked by a contract residing in a namespace are necessarily authorized, defined, and correct for that namespace. This design choice makes fast datalog-style queries against namespaces very convenient and exceedingly useful.

A namespace definition may control the interactions that occur in the space, for example, by specifying:

- Accepted Addresses

- Accepted Namespaces

- Accepted Behavioral Types

- Max/Min Data Size

- I/O Structure

A definition may, and often will, specify a set of accepted namespaces and addresses which can communicate with the agents it defines.

Note the check against behavioral types in the graphic above. This exists to ensure that the sequence of operations expressed by the contract is consistent with the safety specification of the namespace. Behavioral type checks may evaluate properties of liveness, termination, deadlock freedom, and resource synchronization - all properties which ensure maximally “safe” state alterations of the resources within the namespace. Because behavioral types denote operational sequencing, the behavioral type criteria may specify post-conditions of the contract, which may, in turn, satisfy the preconditions of a subsequent namespace. As a result, the namespace framework supports the safe composition, or “chaining” together, of transactional environments.

Composable Namespaces - Resource Addressing¶

Until this point, we’ve described named channels as flat, atomic entities of arbitrary breadth. With reflection, and internal structure on named channels, we achieve depth.

A namespace can be thought of as a URI (Uniform Resource Identifier), while the address of a resource can be thought of as a URL (Uniform Resource Locator). The path component of the URL, scheme://a/b/c, for example, may be viewed as equivalent to an RChain address. That is, a series of nested channels that each take messages, with the named channel, a, being the “top” channel.

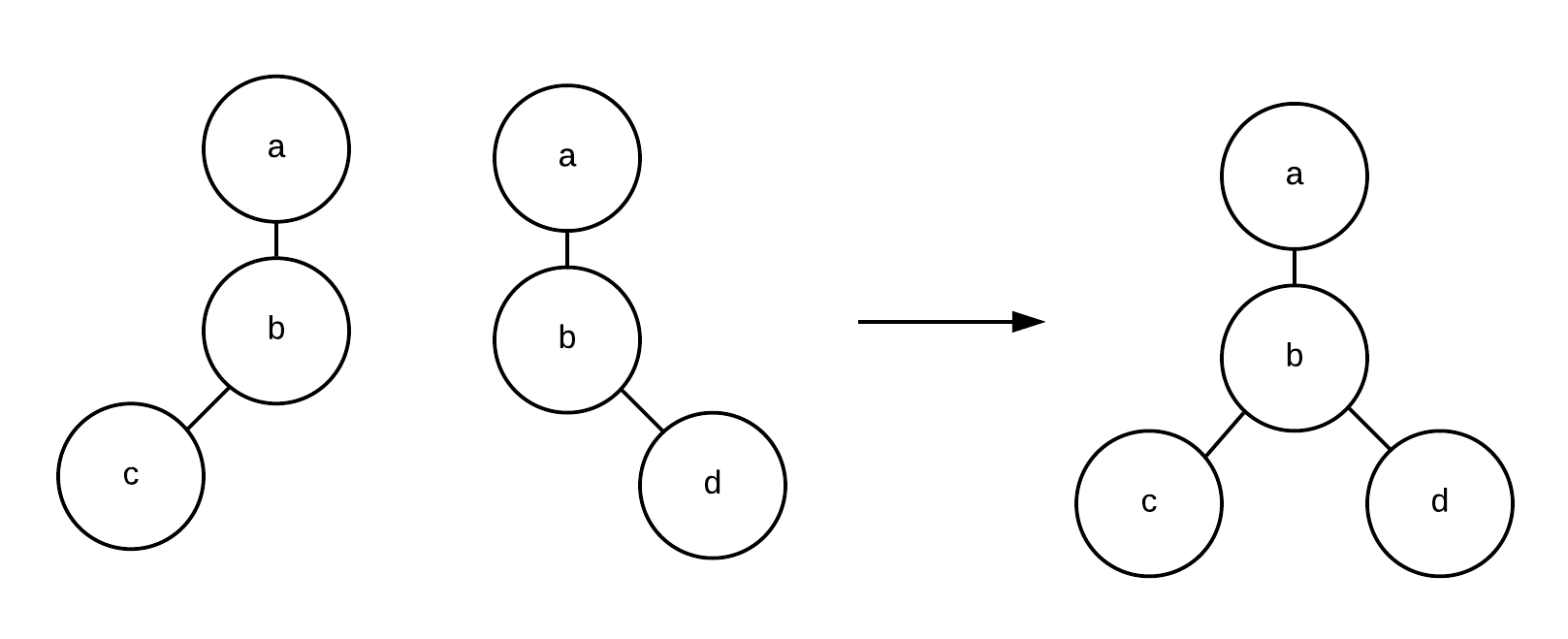

Observe, however, that URL paths do not always compose. Take scheme://a/b/c and scheme://a/b/d. In a traditional URL scheme, the two do not compose to yield a path. However, every flat path is automatically a tree path, and, as trees, these do compose to yield a new tree scheme://a/b/c+d. Therefore, trees afford a composable model for resource addressing.

Above, unification works as a natural algorithm for matching and decomposing trees, and unification-based matching and decomposition provides the basis of query. To explore this claim let us rewrite our path/tree syntax in this form:

scheme://a/b/c+d ↦ s: a(b(c,d))

Then adapt syntax to the I/O actions of the rho-calculus:

s!( a(b(c,d)) )

for( a(b(c,d)) <- s; if cond ){ P }

The top expression denotes output - place the resource address a(b(c,d) at the named channel s. The bottom expression denotes input. For the pattern that matches the form a(b(c,d)), coming in on channel s, if some precondition is met, execute continuation P, with the address a(b(c,d) as an argument. Of course, this expression implicates s, as a named channel. So the adapted channel structure is represented:

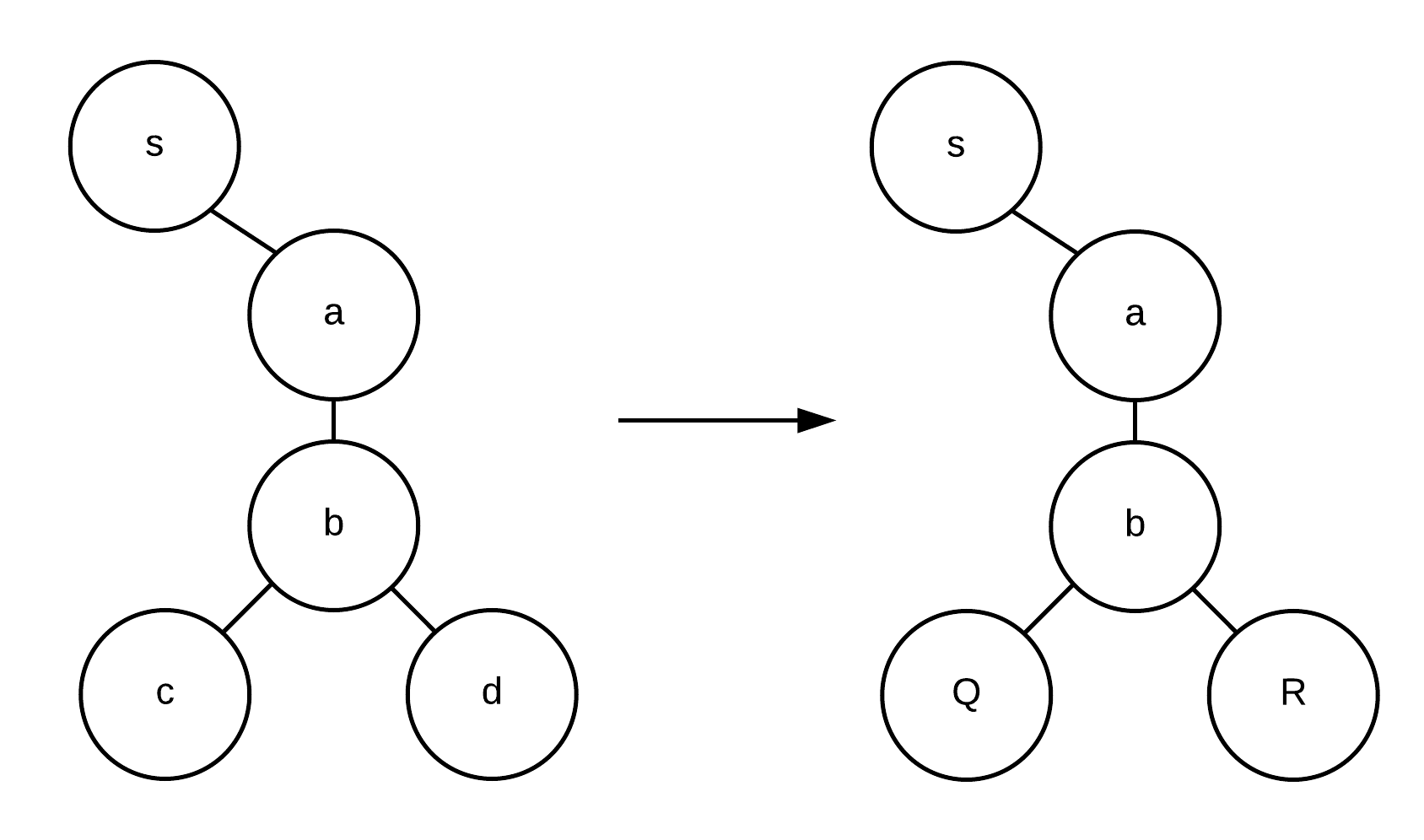

Given an existing address structure, and namespace access, a client may query for and send to names within that address structure. For example, when the rho-calculus I/O processes are placed in concurrent execution, the following expression denotes a function that places the quoted processes, (@Q,@R) at the location, a(b(c,d)):

for( a(b(c,d)) <- s; if cond ){ P } | s!( a(b(@Q,@R)) )

The evaluation step is written symbolically:

for( a(b(c,d)) <- s; if cond ){ P } | s!( a(b(@Q,@R)) ) → P{ @Q := c, @R := d }

That is, P is executed in an environment in which c is substituted for @Q, and d is substituted for @R. The updated tree structure is represented as follows:

In addition to a flat set of channels e.g s1...sn qualifying as a namespace, every channel with internal structure is, in itself, a namespace. Therefore, s, a, and b may incrementally impose individual namespace definitions analogous to those given by a flat namespace. In practice, the internal structure of a named channel is an n-ary tree of arbitrary depth and complexity where the “top” channel, in this case s, is but one of many possible names in s1...sn that possess internal structure.

This resource addressing framework represents a step-by-step adaptation to what is the most widely used internet addressing standard in history. RChain achieves the compositional address space necessary for private, public, and consortium visibility by way of namespaces, but the obvious use-case addresses scalability. Not by chance, and not surprisingly, namespaces also offer a framework for RChain’s sharding solution.

| [5] | Namespace Logic - A Logic for a Reflective Higher-Order Calculus. |